Australia's Housing Shortfall Isn't a Headline, It's a Structural Constraint

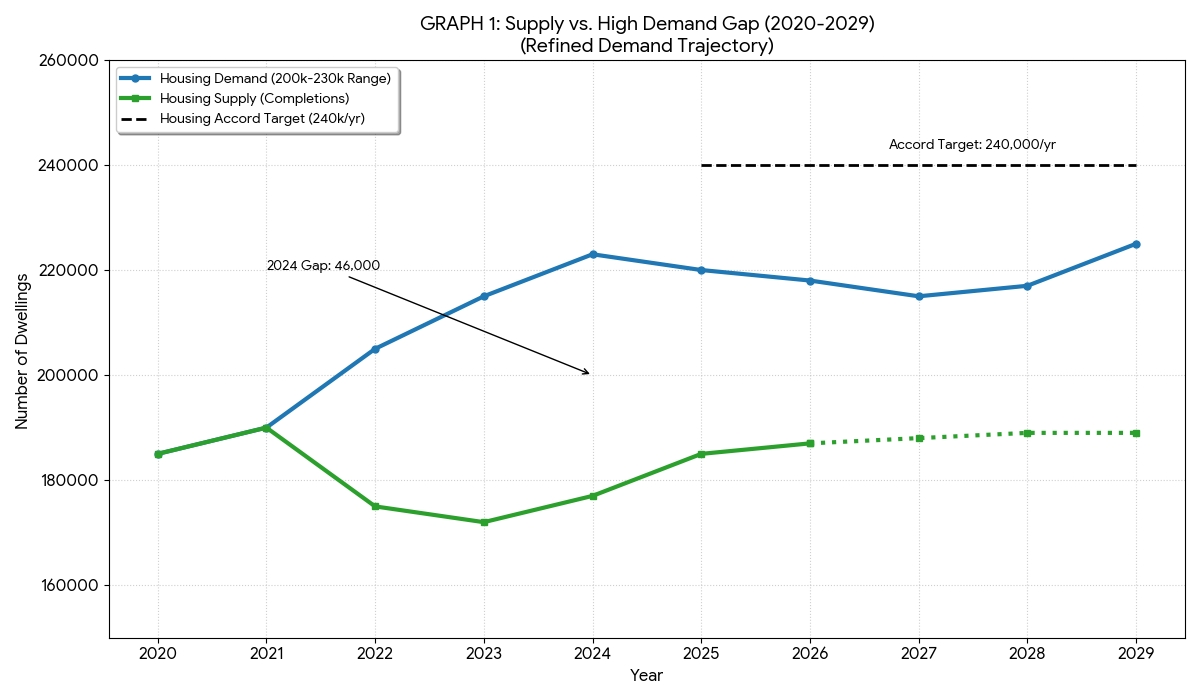

The numbers paint a sobering picture: in 2024, Australia completed just 177,000 new dwellings against an estimated demand of 223,000. This 46,000-unit shortfall isn't an aberration, it's the latest manifestation of structural constraints that have been calcifying in Australia's housing system for decades.

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council's State of the Housing System 2025 report confirms what many Australians already forecasted. The nation is projected to fall 262,000 dwellings short of the National Housing Accord's ambitious 1.2 million home target by mid-2029. More critically, after accounting for demolitions, net new housing supply will trail underlying demand by 79,000 dwellings over the five-year Accord period.

This isn't a crisis that materialised overnight - it's the product of structural impediments embedded deep within Australia's construction industry, planning systems, and economic framework.

The Productivity Paradox

Perhaps the most startling revelation comes from the Productivity Commission's recent examination of the housing construction sector. Physical productivity, the total number of homes built per hour worked, has plummeted by 53% over the past 30 years. Even when accounting for improvements in home size and quality, labour productivity has declined by 12%.

During the same three decades, labour productivity across the broader Australian economy increased by 49%. If housing construction had merely kept pace with this national trajectory, average Australian incomes would be approximately 41% lower than they are today. The productivity gap isn't just a construction industry problem, it's a drag on national prosperity.

Construction costs have surged 40% in just five years, while residential build times have stretched by up to 80% over the last 15 years. These aren't market fluctuations; they're symptoms of fundamental dysfunction.

The problem is multifaceted. Australia's construction sector is dominated by microbusinesses - 91% have fewer than five employees, more than double the proportion from the late 1980s. The Committee for Economic Development of Australia estimates that if building companies achieved the scale typical of manufacturing companies, the sector could generate an additional $54 billion in annual revenue with the same workforce. That's equivalent to an extra 150,000 construction workers, but without having to recruit a single person.

The Feasibility Crisis

Beyond productivity, Australia faces what the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council identifies as a critical feasibility crisis. The Council states that "the single biggest constraint on supply currently is that many housing projects are not commercially viable given current land, financing and development costs relative to expected sale prices."

Higher-density projects face particular challenges. Price growth for apartments and units has lagged behind detached dwellings, while financing costs for these projects have escalated disproportionately due to larger loan requirements and extended construction timelines. When combined with labour shortages and material price volatility, the result is a perfect storm of development paralysis.

The Affordability Chasm

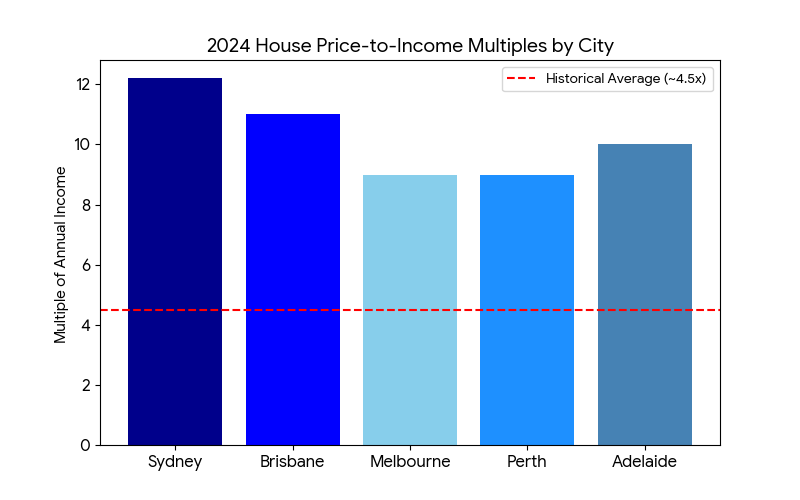

The human cost of these structural constraints is measured in years. Specifically, the 10.6 years the average household now requires to save for a deposit. The house price-to-income ratio has nearly doubled since 2002, with the average Australian home now costing approximately nine times the average household income.

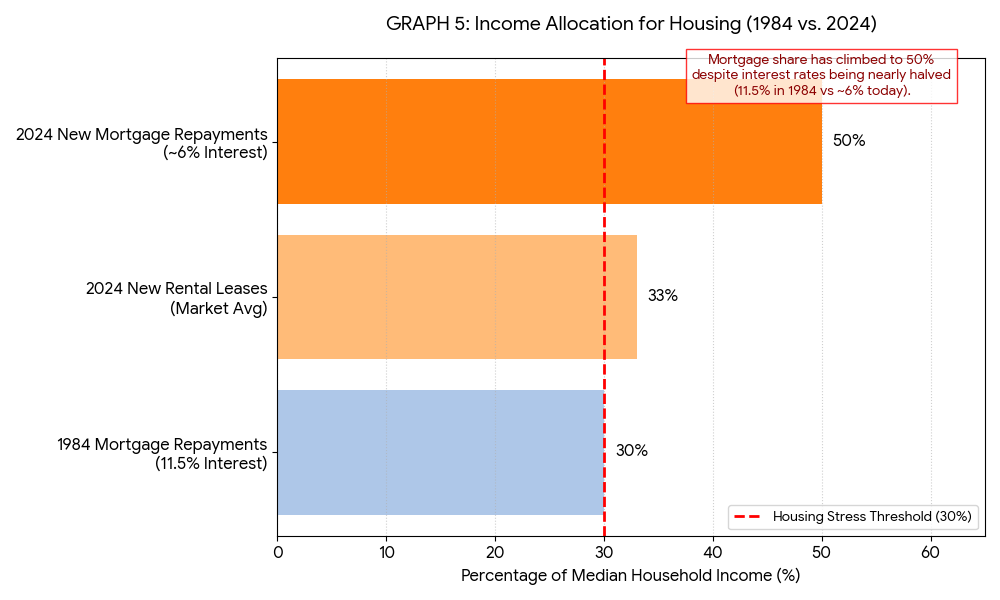

In December 2024, 50% of median household income was required to meet mortgage repayments for new loans, while 33% went toward rental costs for new leases. These aren't sustainable ratios. They represent a fundamental breakdown in the relationship between housing costs and earning capacity.

Historical perspective sharpens the picture. In 1984, the average home cost 3.3 times the average annual income. By 2025, that multiple had ballooned to 9.4. Even accounting for lower interest rates today compared to the double-digit rates of the 1980s, Australians spend a far greater proportion of their income on housing.

The Planning Labyrinth

Australia's planning and approval systems amplify these constraints. The Productivity Commission characterises Australia as having "the most decentralised system of land-use planning in the OECD." This fragmentation creates a complex web of overlapping regulations across federal, state, and local government levels.

The National Construction Code, while sound in principle, interacts with state and local regulations in ways that impose unnecessarily high construction costs. State-based occupational licensing restricts labour mobility, preventing workers from easily relocating to areas where demand is highest. Despite automatic mutual recognition agreements, numerous exemptions and conditions persist, limiting the construction industry's ability to respond dynamically to market signals.

Planning approval processes are slow, poorly coordinated, and under-resourced. Local councils, tasked with making critical development decisions, often lack the capacity to process applications in a timely manner. The result is a system that acts as a brake on housing supply, even when market demand is clear.

The Demand Side Continues

While structural constraints throttle supply, demand continues unabated. Net overseas migration remains at historically elevated levels, with net permanent and long-term arrivals reaching record highs through 2025. Former senior immigration department bureaucrat Abul Rizvi estimates that under current policy settings, net overseas migration will average around 300,000 annually - 15% higher than Treasury forecasts.

Average household size continues to decline, a demographic trend that increases housing demand independent of population growth. The share of Australians who rent rather than own has increased from 25% in 1981 to 31% in 2021. Many of these renters aspire to homeownership but find themselves priced out - only half of current renters expect to own a home in their lifetime.

The Innovation Deficit

The construction industry's resistance to innovation compounds productivity challenges. Building techniques remain largely unchanged from decades past, with prefabrication and modular construction still marginal practices despite their potential for efficiency gains. Regulatory frameworks haven't adapted to encourage new construction methods, while a fragmented industry structure makes it difficult for innovative approaches to achieve scale.

The industry's cyclical nature, with pronounced swings in demand, encourages short-term contracting arrangements over long-term capacity building. Large infrastructure projects compete for the same skilled labour pool as residential construction, creating persistent shortages that drive up costs and extend timelines.

The Public Sentiment

Australians are acutely aware of these failures. Gallup polling in 2024 found that 76% of Australians were dissatisfied with housing availability and affordability - a record level of discontent. Only 22% expressed satisfaction. Among OECD countries, only Turkey reported higher dissatisfaction.

The contrast with other infrastructure and services is striking. Clear majorities of Australians remain satisfied with healthcare (71%), schools (66%), roads (60%), and public transportation (61%). Housing stands alone as the area where Australia's systems are failing its citizens.

A Structural Reckoning

The evidence is overwhelming: Australia's housing shortfall is not a cyclical problem awaiting a market correction. It is a structural constraint that will not resolve without comprehensive reform across multiple domains.

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council identifies five critical policy areas requiring urgent attention: increasing social and affordable housing investment; improving construction sector capacity and productivity; reforming planning systems; providing enhanced support for renters; and ensuring taxation settings support rather than undermine housing supply and affordability.

The Productivity Commission recommends streamlining planning approvals, independently reviewing the National Construction Code, achieving national consistency in occupational licensing, and removing impediments to construction innovation.

These are not quick fixes. They require sustained political will, coordination across government levels, and a willingness to challenge entrenched interests and outdated regulatory frameworks.

The Path Forward

Australia stands at an inflection point. The structural constraints that have slowly strangled housing supply over three decades are now producing acute, visible crises: a generation priced out of homeownership, renters spending unsustainable proportions of income on housing, and families making impossible trade-offs between shelter and other necessities.

The question is no longer whether reform is needed, the data makes that answer unequivocal. The question is whether Australia's political and economic institutions can muster the resolve to dismantle the structural barriers they have, through decades of incremental decisions, constructed.

The housing shortfall isn't a headline. It's a structural constraint that touches every aspect of Australian economic and social life. Treating it as anything less guarantees continued deterioration of one of the most fundamental determinants of wellbeing and prosperity.

The Investor Opportunity?

These structural constraints create predictable demand patterns in specific markets.

At PWF, we help everyday Australians build wealth by identifying high-growth locations where these constraints are most acute. Areas with strong employment, limited supply, and growing populations. We don't fight the system; we understand it and position our clients strategically within it.

Our clients get:

✓ Access to vetted builders who price fairly

✓ Market intelligence on realistic construction costs

✓ Strategic investment in high-growth locations

✓ Cashflow-positive portfolios built on solid foundations

✓ Protection from gouging at every stage

Over 20 years, we've helped 4,000+ Australians build property portfolios that generate passive income and long-term wealth, even in constrained markets. Reach out here if you’re interested in learning more.

This article has been based on data from the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, Australian Productivity Commission, Australian Bureau of Statistics, and Reserve Bank of Australia.